NHIs are here, performing countless actions on our behalf. Understanding them begins with seeing that every non-human identity represents accountability, not just automation, and approaching it from how NHI management is more than just a technical discipline. It is about ownership and governance across change and access processes. To set up that governance, organisations must recognize where NHIs live in their architecture and assign accountability accordingly.

This article continues the NHI discussion started in Part 1 by examining how non-human identities come into existence, operate, and are decommissioned. Just like human users follow Joiner-Mover-Leaver (JML) logic, NHIs follow their own pattern — one rooted in change management.

Lifecycle of NHIs

Just like human identities, NHIs have a lifecycle. Somehow, they come to exist, they have a life, and then they are destroyed.

For human identities, the human resource management (HRM) processes are the governing processes. Joiner–Mover–Leaver (JML) is the core model. Every Join, Move, or Leave event will be evaluated for the identity and access management consequences. If an actor joins an organization, a digital identity is created, and one or more accounts or usernames are assigned to this actor. Moving within the organization (to a new department or manager) will result in a reevaluation of permissions. And when leaving, all permissions will have to be revoked and licenses will be terminated, all to prevent the abuse of identities and identity theft.

For non-human identities, a different process is the governing process, not the JML processes. These processes are not HR processes. NHIs don’t apply for a job, nor do they drop out of the sky.

Before NHIs gain access to the network or a building, they must be onboarded. Meaning they should be identifiable as ‘trusted’ components that may get access for a defined purpose. A component has a purpose, a goal in non-human life. Be it a service, a server, a robot, Robotic Process Automation (RPA), or a machine interface. The component is implemented and configured for that purpose. The governing process is a Change Management process, and registration occurs in a configuration management database (CMDB). Reconfiguring the component to serve a different purpose or work in a different environment is possible, but that also requires a change. A financial reporting RPA will not become an invoicing RPA without reconfiguration, not without a change request. And removal of the component, again, takes a change.

So instead of JML, this is Create, Adjust, and Remove. We could refer to this as the CAR processes or, less specifically, change management.

Change Management

A change management process is more than just the Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL) definition; it’s every change in an infrastructure or application landscape that results in functionality or features needed.

There is always a stakeholder who requests functionality: a tool, a service, or whatever. If the stakeholder has the mandate to do so, a change will be implemented, resulting in a component, service, or thing that can be used by or on behalf of the stakeholder. And, this is key: a change not only results in the component, but also in a governance item, typically the registration in a configuration management database (CMDB). And it is important that the CMDB item affected by the change has an owner and some more documentation, like the permissions needed by the component. We know who requested the component, we know its whereabouts, and we know the permissions.

Changing the functionality or location of the component is possible, but that, again, requires a change request and documentation. This is also valid for all components, including those built dynamically, such as services created in a CI/CD pipeline. The continuous process is a configured process; it has an owner, a build requester. So even those services and APIs are created in a structured and governed manner, and that again is a change management process. And even more, these processes can be part of automation (in CI/CD devops environments) or procurement processes. The changes (such as in the source code and config files) may even be documented in a version control system in highly automated build processes.

When the component is not in use anymore, it will be decommissioned, it must be disabled, removed, or destroyed. When the component has no purpose anymore, the final change is the removal of the component and registering the change in the CMDB. It must not be removed from the CMDB, because it once had its own identity, and for logging, monitoring, and forensics purposes, we need to know the history of the component.

Remember that maintaining the CMDB is an ongoing process; this precondition will not be discussed further.

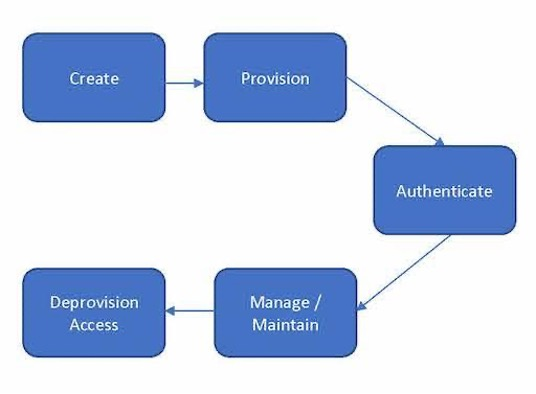

As a further clarification, the digital identity lifecycle of non-human accounts, as defined in IDPro (see refs) is shown:

Figure 1: NHI lifecycle

IGA and Authorization

To automate the Human JML process, the supporting tool is an Identity Governance and Administration (IGA) solution. It evaluates the event in an HR system and, based on rules and roles, provisions accounts and authorizations to connected target systems. And after provisioning, it can also reconcile the target systems to validate accounts and permissions in these target systems.

In this process, the IGA system will encounter accounts and authorizations that have not been generated by the IGA system. IGA will see the admin and root accounts that belong to the target system. These accounts are NHIs, and they exist as a part of the target system. If you implement a new Linux or Windows server, the root or admin account already exists. And, as you will understand, these new servers are the result of a change management process; it’s not a JML event.

After reconciliation (the process of reading back the identity and authorization repositories of a target system), an IGA system will see the root or admin account in the target system, and that’s it. No need to manage admin or root as these accounts have all permissions, as they should have. They will not be related to a human identity. The account belongs to the component, and it also has an owner: the owner of the component. IGA will see the account and report it as ‘not being managed by IGA’, but that’s okay. In most IGA solutions, this type of account can be classified as a system account or service account. In fact, IGA solutions should enable it to be classified as an NHI.

In short, IGA takes care of human access as a result of the human JML process. But where does that leave the NHI’s, how should we manage their lifecycles?

For human identities the lifecycle management process is well defined and IGA systems are well equipped to support that with both account management and role based access control, provisioning and deprovisioning accounts and authorizations. Can the same system also support NHI’s? And then my opinion is that IGA systems should not be the solution to manage the lifecycle of NHI’s. And there are multiple reasons for that. First, there is not just one process responsible for managing NHI’s.

If you treat an NHI as a human identity, some additional controls are inevitable: If you would manage the lifecycle and authorizations of an NHI in en IGA solution, then these effects would be caused by the IGA solution:

- An account is created in the target system through the provisioning process;

- In the organizational structure of, not sure, either the org top level structure, or a sub level of the top level, to be defined by the owner? Or Manager or operator?;

- The birthright authorizations will be granted for the org top level;

- The line manager will see the NHI to grant authorizations by assigning a role.

But these provisioning effects have to be undone, because other controls and measures are already in place:

- Account creation has already been done by onboarding the NHI in the network;

- There is no need to assign the NHI to an organizational level: in the CMDB or change request the whereabouts of the component is already known;

- The NHI shall not have default birthright authorizations or roles, components don’t need birthright authorizations, they only need ‘least privilege’ access;

- The NHI doesn’t need a role, it has all the required permissions defined/described in the change. An RPA cannot just get new authorizations by changing the business role in IGA, it needs new functionality, because of the change.

And the same will happen for other NHIs: say we configured an RPA. Every day after office hours the RPA will read the sales figures, analyse the data, create a report and send the report to the head of sales. This RPA needs an account, authorisations, and resources to perform these actions. All of this will be configured while creating the NHI.

The NHI will work on behalf of the Head of Sales, but it should not have the authorizations of the Head of Sales. Nor shall it have the business role of the Head of Sales, it only needs the permissions needed to read, analyze, create, and distribute the report. Least privilege. The permissions are very specific. Any other RPA will have different authorizations, no need to make a role for it. Its authorizations are a dedicated, non-reusable set of permissions. And these permissions will not be changed, unless the functionality of the RPA must change, in which case it will be newly developed. RBAC? No way! In fact, if you try to give a role to an NHI, you misunderstand the concept of RBAC… There are better solutions for managing access for NHI’s, like Policy Based Access Control or Relation Based Access Control to add the dynamics required. We will get to that in the next articles in this series.

Life Cycle Conclusion

NHIs don’t join the organization. NHIs are managed through a change management process. This means that an IGA solution does not fit the NHI lifecycle management process. IGA vendors may tease you in managing NHIs in IGA, but that’s not a sustainable solution.

NHIs must be managed in a change management process, and they should be registered in a CMDB and assigned to an owner.

Reality check

No, this hardly ever happens. In most organizations any CMDB is not reliable, the registration is, therefore, unreliable. But that should not keep you from managing NHIs in a controllable way. This is a call for fine-tuning the change management and asset management processes.

The organization may decide to implement specific tooling for managing NHIs, that’s all right, but that does not mean that the governance problem can be ignored. There must still be a business owner who is accountable for the life cycle and the authorizations granted. And just implementing additional tools next to the CMDB and service management solutions that are in place could only obfuscate the problem of lack of governance.

Conclusion

This lifecycle perspective underlines one essential truth: NHIs are governed through change, not employment. The Access article examines how these identities interact with systems. Specifically, how access “to” and “by” NHIs should be understood and controlled.

References

There are great resources that cover NHIs, but the lifecycle covered in this article are not clearly identified. Anyway, please study these articles in the IDPro Body of Knowledge:

- IDPro: Non-human account management: https://bok.idpro.org/article/id/52/

- IDPro: Digital Identity Lifecycle: https://bok.idpro.org/article/id/31/

The CAR case was invented by my colleague Henk Marsman, feel free to use CAR 🙂

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the content are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IDPro organization.

About the author:

André Koot is principal IAM consultant at Dutch IAM consultancy and managed services company SonicBee (an IDPro partner). And member of the Advisory Board of IdNext.eu. He has over 30 years of infosec experience and over 20 years of experience as an IAM expert, acting as architect, auditor and program lead. For the last nine years he has taught a 4-day IAM training course. André contributes to the IDPro BoK as committee member, author, and reviewer.