Following the article about NHI’s and their lifecycle , this final article in the series explores how non-human identities interact with systems. It focusses on access, permissions, and the dual nature of “access to” and “access by.”

Access and NHIs

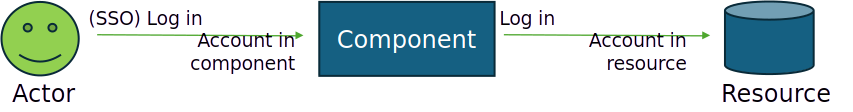

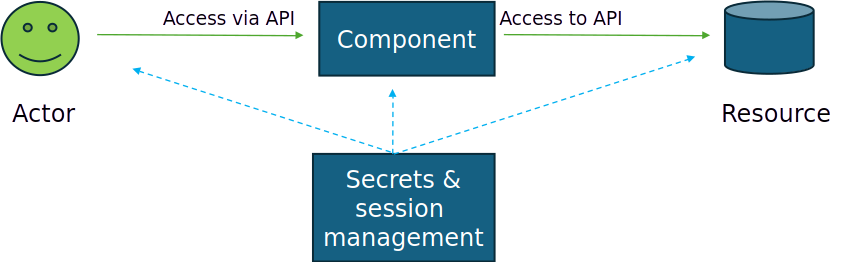

There are some interesting observations to be made about access control and NHIs. And missing these views leads to misunderstanding NHI Access Control and results in conflicting advice and practices. Access control and NHI’s have at least 2 different aspects: Access to the component and Access by the component. And these different views can be evaluated in this visualization:

Figure 1: Access to and access by an NHI

In this illustration, an actor logs in to a component interactively. The actor has an account and authorizations to match. Accounts and authorizations are dependent on the J-M-L-process and probably Role Based Access Control.

The component in turn, logs into a resource, probably using a resource account and authorizations. Since the login is automated, the secret to login with is probably configured in the component. In this pattern, the component could be an application that gives access to the actor, and the application will login to the resource (potentially a database server) with a service account. The component could also be a camera, or a device.

This simple pattern shows two views on access: Access to the component and access by the component.

Permissions

As we discussed before, NHIs, Non-human Identities, are managed in the change management process and these identities belong to components, such as servers, robots (and RPA’s), devices, services and what not. And these components have a purpose in life. They perform tasks. And to do so, they need to have the correct permissions.

Relevant here is that from a governance perspective, we must have the possibility to validate what actions the component has performed. It must be traceable; it must be recognizable: this task or transaction has been performed by this component. This is in fact where the concept of NHI is born: the component needs an identity, it needs an account and it needs authorizations in order to perform the tasks.

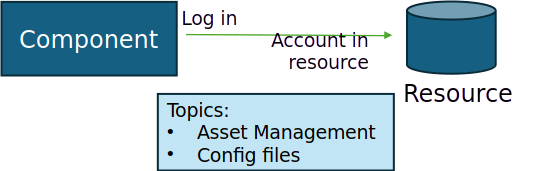

Figure 2: NHI needs access

So, the NHI is an identifier to grant authorizations to and to enable logging, monitoring and traceability of transactions performed by the NHI in the resource.

Authorizations granted will be defined following the Least Privilege principle: grant at most the authorizations that are minimally required to perform a task. Nothing more, nothing less. And the permissions needed are given based on the functional requirements of the tasks to be performed.

In creating the change and during development of any component that will need an NHI, all relevant stakeholders must be contacted to give their views on granting permissions to the NHI. If the NHI belongs to a camera, it needs the authorization to access the network (an IP address), and it needs the permissions to store video images on a server and perhaps it even needs the permissions to send a notification to facility management. And so, the stakeholders are facility management, network management, server management, security management and probably also a privacy officer. All stakeholders have to define the least privileged authorizations.

That’s the easy part of access control: the NHI needs access to the systems it connects to and it needs the authorizations to perform the tasks that it was implemented for.

Login to the NHI

But there’s a second viewpoint to NHIs: actors who need access to the NHI. In the camera example: who can use the pan and zoom functions of the camera?

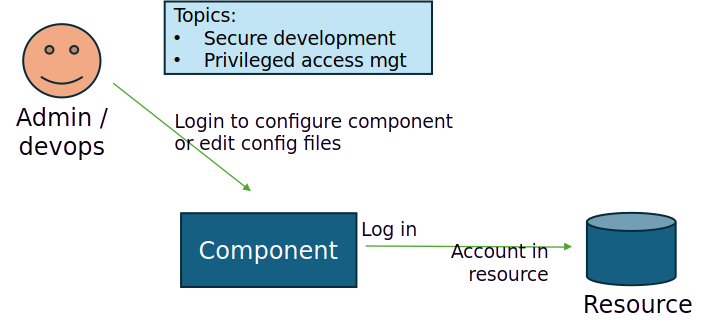

An example of this type of access is a component like an RPA. The RPA has access to resources. The authorizations to the resource are custom authorizations, least privilege dependent on the purpose of the RPA. The second view is: who has access to the RPA. The RPA is developed and configured by an admin or operator who can either configure the code of the RPA or change the config files to comply with the functional requirements. Since the actions change the behavior of the RPA, special authorizations and logging and monitoring are required to manage access.

And here the picture becomes cloudy. There can be lots of stakeholders who need access.

First there is the operator, the actor who manages and configures the NHI. An NHI must be managed. There is a config. Either in a config file or in the database or even in the connector. And perhaps this operator must log in to the component. There may be an internal admin account in the component. Yes, we covered that: a server has an admin account, and the server has an identity. And the admin account will be found on the network. Just like the server will be found.

Let’s have a look at this same camera: it has an IP address and perhaps a DHCP-name and there must be one or more accounts that can be accessed. There is the admin-account and perhaps an operator account, potentially a read-only account and, speaking of cameras, a backdoor account to upload malware…

And there may be an on-board webserver, with again an NHI, an account and permissions. It never ends…

Anyway, there are accounts to log in to, to get access to the component, with a default factory (-reset) password for the admin account. Yes, these secrets live in the open.

Figure 3: DevOps and NHIs

APIs anyone?

And now to make the issue even bigger:

Some components not only offer login features, but they may also have APIs to give access to inner application functions. And this gives us a second access problem: who can access the APIs? What controls do we need to enforce to secure the endpoints? And this is where the concept of access control based on keys and tokens is needed. A second secrets management point

… A second secrets management point of view. I will not dive deeper into this concept of API access and whether we need API gateways, policy enforcement points and policy management points to manage fine grained dynamic access to the component. But we need a trusted facility to manage secrets and sessions.

Figure 4: NHIs and secrets

Access Control Conclusion

There you have it: Access by the component requires an NHI identity and account, for granting authorizations and for auditability purposes. But the NHI is accessed too. Login to the NHI and API access to the NHI require different controls. And both concepts cannot be mixed. The NHI needs resources, hence it needs an identity, and the NHI is a resource, hence we will have to restrict access.

This access perspective completes the NHI picture. Lifecycle defines how NHIs come into being and are governed; access defines how they interact within systems, both as consumers and as resources themselves. The takeaway is simple yet often overlooked: NHI access must be designed and audited in two directions. Treating them as human users oversimplifies the problem; treating them as governed, purpose-built components restores clarity and control.

About the Author:

André Koot is principal IAM consultant at Dutch IAM consultancy and managed services company SonicBee (an IDPro partner). And member of the Advisory Board of IdNext.eu. He has over 30 years of infosec experience and over 20 years of experience as an IAM expert, acting as architect, auditor and program lead. For the last nine years he has taught a 4-day IAM training course. André contributes to the IDPro BoK as committee member, author, and reviewer.