The U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) recently (as of July) completed its final paper on the pillars of Zero Trust. While the NSA does not directly credit it, these pillars conform to the U.S. Department of Defense’s (DoD) Zero Trust Reference Architecture, which IDPro had previously discussed. It would be beneficial to understand if there are any differences in the messaging between the NSA and DoD, what those differences are as they relate to identity, what similarities there are, and perhaps what we might glean from each organization’s representation of identity from a publicly facing perspective.

How Each Organization Wants Us To “See” Zero Trust

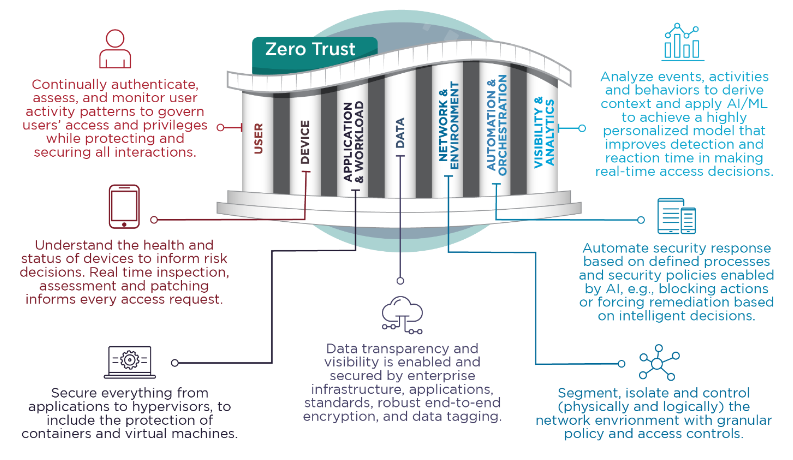

The NSA defines each “pillar” of zero trust as separate capabilities, each with a clear purpose and demarcation. While not entirely independent of each other (for instance, some aspects of the device pillar may intertwine with the user pillar, and so on) there are clear capabilities that each pillar has all its own. Under this visual model, we still need each capability to do the job of zero trust, and it is implied that each pillar is required for the model to function.

Figure 1: NSA’s Zero Trust Pillars from the NSA CSI series on Zero Trust

The DoD defines each “pillar” as being in service of protecting data. Data is, per the DoD’s understanding, part of all other resources. In this sense data is a pillar, but because everything else utilizes data and the goal is to protect data, the boundary of what is in the data pillar and what is data in service of another pillar gets blurry – for instance, contextual information around a user that guides authorization decisions could absolutely be considered data, and it comes down to the purview of the person looking at the model to make that distinction. The model is further blurred by noting that a given capability may be the purview of multiple pillars and that some capabilities (such as continuous multifactor authentication) span all pillars.

Figure 2: DoD’s Zero Trust Pillars from the DoD ZTRA

What The NSA Reports Offer

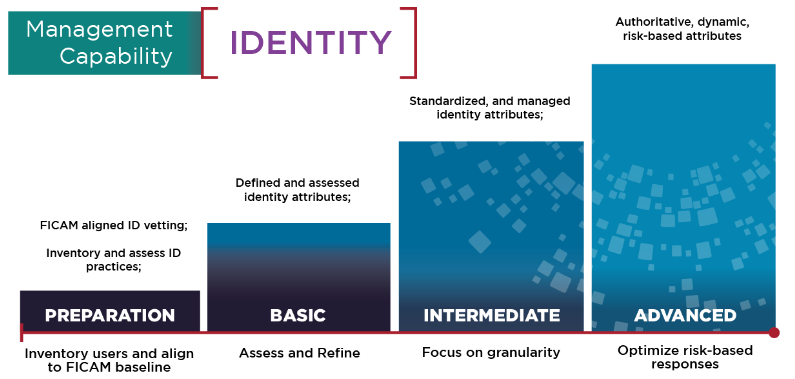

At a high level, the NSA Cybersecurity Information Sheets (CSIs) on Zero Trust (available in totality on the NSA website) generally speak to the capabilities inside a given pillar, how the NSA defines these capabilities, and then the path from preparation into maturity with a given capability. For instance, the NSA speaks to five specific capabilities it feels are within the User pillar. Here we replicate their statements on these capabilities:

- Identity Management: technical systems, policies, and processes that create, define, govern, and synchronize the ownership, utilization, and safeguarding of identity information to associate digital identities to an individual or logical entity.

- Credential Management: technical systems, policies, and processes that establish and maintain a binding of an identity to an individual, physical, or logical entity, to include establishing the need for a credential, enrolling an entity, establishing and issuing the credential, and maintaining the credential throughout its life cycle.

- Access Management: management and control of the mechanisms used to grant or deny entities access to resources, including assurances that entities are properly validated, that entities are authorized to access the resources, that resources are protected from unauthorized creation, modification, or deletion, and that authorized entities are accountable for their activity.

- Federation: interoperability of ICAM with mission partners. This CSI only discusses the general complexity of identity federation.

- Governance: continuous improvement of systems and processes to assess and reduce risk associated with ICAM capabilities. This CSI addresses improvements for this category by defining maturity levels for each of the ICAM categories rather than discussing maturity of identity governance in general.

These statements are fairly broad, and rightfully so. Each capability is discussed in further detail within the CSI, specifically around what an increasingly mature organization might have in terms of capabilities. For instance, if we look at identity management it speaks to a set of capabilities that becomes increasingly complex and based around the mitigation of risk.

Indeed, across the User pillar the NSA makes it clear that they see the mitigation of risk through the utilization of dynamic assessment and recording of risk to push decisions as close to the application and as close to real-time as possible as an “advanced” capability. If we perform a similar analysis of the NSA’s work on the other zero trust pillars, we see a similar building upon prior capabilities to meet a common end goal. For instance, if we look at the automation and orchestration pillar, we see a series of capabilities whose ultimate goal is to support the automation of workflows and to facilitate responses that are dynamic and risk-based. This framing across the NSA CSIs is consistent – drive decisions through each pillar that are dynamic, adjusted for risk, and as close to the application or workload as possible.

As a final note, the NSA CSIs also offer a “why all of this matters” for each separate paper. For instance, the user pillar CSI discusses several real-life scenarios that came about due to ICAM immaturity at a federal level and what the results of those failures were to emphasize each pillar’s importance.

Comparison to the DoD

The DoD ZTRA, by comparison, speaks to specific capabilities that should comprise each pillar and then uses cases that drive the need for these capabilities. For instance, if we look at the “Pillars, Resources, and Capability Mapping” figure in the ZTRA, we see a substantial number of terms and capabilities put forward all at once.

Figure 4: The US DoD’s Zero Trust Reference Architecture Pillars, Resources & Capability Mapping (CV-7)

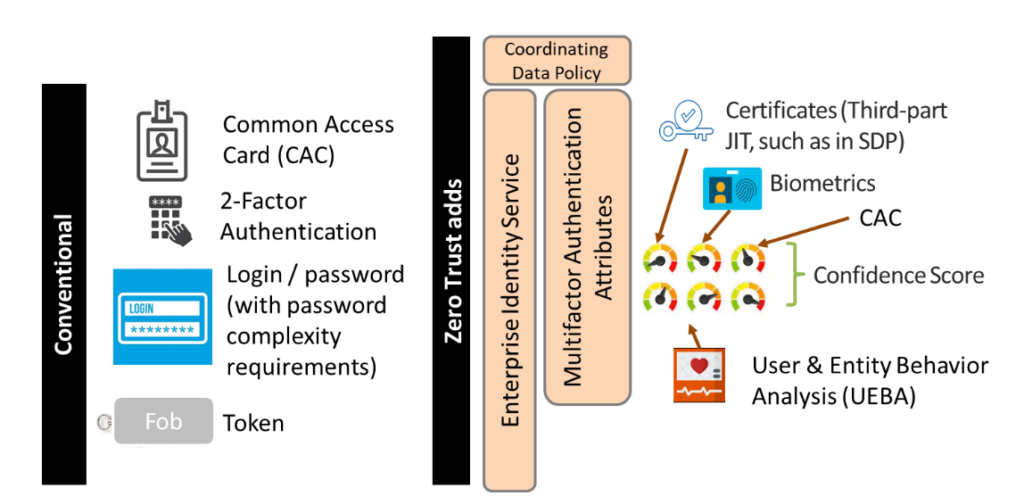

The capabilities outlined here are discussed later within the document – for instance, if we look at the user pillar and its call-out of an Enterprise Identity Service in service of the user pillar, we see the capabilities defined and key functions discussed. Perhaps due to the sheer scale of the mapping done here, we should note the above figure is not exhaustive! We can see this when we look at the use cases. For instance, if we look at the figure representing Use Case 4.14 (Dynamic, Continuous Authentication (OV-1)), we see it fleshes out the capabilities and requirements further.

Figure 5: The US DoD’s example of Dynamic, Continuous Authentication (OV-1)

Differences and Similarities Between the DoD and NSA

It could be said that between the two US Government sources on zero trust thought leadership, the Department of Defense is more focused on speaking to specific capabilities it feels are necessary to eliminate implicit trust across the organization with the ZTRA. The NSA, in its CSIs, is attempting to offer a path by which an organization might eliminate implicit trust. While the DoD does speak on needing a dynamic and risk-adjusted response for each action taken in the environment, it at times loses that messaging over spelling out the capabilities it feels are necessary to get there.

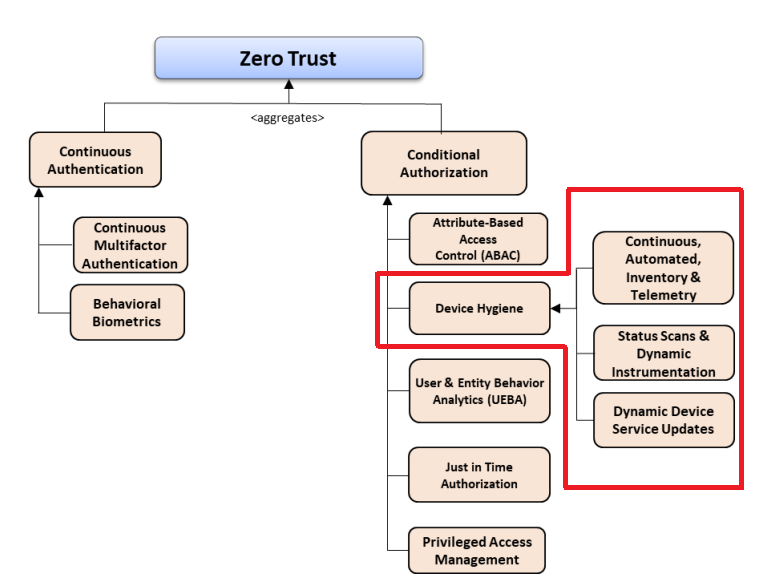

The NSA’s CSIs offer a clear advantage here in that they attempt to educate as opposed to enumerate but at the expense of perhaps missing things that may be considered important to a given pillar. For example, within access management, the NSA CSI on the user pillar discusses privileged access devices generally, which suggests some implicit trust of the workstation itself. The DoD’s model, in the “Zero Trust Authentication and Authorization Capability Taxonomy (CV-2)” figure, instead calls this “Device Hygiene” and calls out specific capabilities that comprise this capability.

To the NSA’s credit, they discuss these capabilities in further detail within the Device Pillar CSI, and to the NSA’s further credit, they specifically state that pillars are not independent, and many capabilities rely on or mesh with other capabilities in other pillars. All of that said, for an individual or organizational unit looking to understand where they fit into zero trust it can be a lot like grasping at an elephant in the dark if they only read about the pillar that relates to their daily operations. The DoD ZTRA, in comparison, does not have this sort of by-pillar problem due to it presenting all the work in one place.

These differences are largely in the way the information surrounding zero trust is disseminated to its audience, and who its audience is. The DoD ZTRA is very much for stakeholders within the DoD. The NSA CSIs are very much for the larger federal government (both within defense as well as national security). The DoD ZTRA is very much a reference architecture, and it is built to discuss specific use cases that the DoD considers important to solve. The NSA CSIs are built to help organizations understand the path to zero trust, which has unfortunately been used more as a term by security firms to sell products and less as a framework in which to mitigate risk through the elimination of implicit trust.

The commonalities between these works are significant. Both the DoD ZTRA and NSA CSIs on zero trust act as some of the most (if not the most) comprehensive, definitive visions of zero trust available today to the public. Both are very clear about the necessity to eliminate implicit trust and the need to radically shift how organizations think about identity and its associated capabilities. Both are excellent, no-nonsense reads that are vendor-neutral. Both promote a strategy that, as adversarial events become both more frequent and more sophisticated, makes sense to explore and adopt. It would be prudent for any organization looking to mitigate risk to understand what governments are doing to address nation-state level adversaries, and consider what steps they could take to bolster their own internal processes.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the content are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IDPro organization.

Author

Rusty Deaton has been in Identity and Access Management for over a decade. He began in technology as a technical support engineer for a Broker-Dealer and has since worked across many industries, carrying forward a passion for doing right by people. When not solving problems, he loves to tinker with electronics and read. He currently works as Federal Principal Architect for Radiant Logic.

Rusty Deaton has been in Identity and Access Management for over a decade. He began in technology as a technical support engineer for a Broker-Dealer and has since worked across many industries, carrying forward a passion for doing right by people. When not solving problems, he loves to tinker with electronics and read. He currently works as Federal Principal Architect for Radiant Logic.